NEW YORK (AP) - Whatever success Republicans have amassed in taking control of all three branches of U.S. government, and whatever fate awaits them as midterm elections near, some on the right are working to cement change by amending the Constitution. And to the mounting alarm of others on all parts of the spectrum, they want to bypass the usual process.

They're pushing for an unprecedented Constitutional convention of the states. While opponents are afraid of what such a convention would do, supporters said it is the only way to deal with the federal government's overreach and ineptitude.

"They literally see this as the survival of the nation," said Karla Jones, director of the federalism task force at the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council, which represents state lawmakers and offers guidance and model legislation for states to call a convention under the Constitution's Article V.

Among the most frequently cited changes being sought: amendments enforcing a balanced federal budget, establishing term limits for members of Congress, and repealing the 17th Amendment, which put the power of electing the Senate in the hands of the public instead of state legislatures.

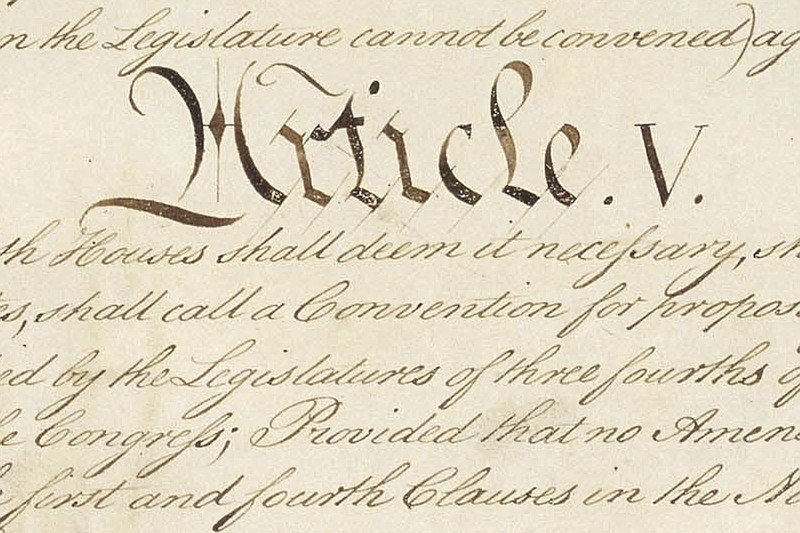

For the past 229 years, constitutional amendments have originated in Congress, where they need the support of two-thirds of both houses, and then the approval of at least three-quarters of the states.

However, under a never-used second prong of Article V, amendments can originate in the states. Two-thirds of states - currently, 34 - must call for a convention at which three-fourths of states approve of a change.

The particulars of such a convention, though, are not laid out. Do the states have to call for a convention on the same topic? Must they pass resolutions with similar or identical wording? The U.S. Supreme Court may have to decide whether the threshold of states has been reached and, ultimately, the parameters of a convention and the rules delegates would be governed by.

A bill introduced in the U.S. House last year would direct the National Archives to compile all applications for an Article V convention.

Some believe enough states have already passed Article V resolutions, pointing to votes over the years across the country on a variety of potential amendment topics. Others contend the highest possible current count of states is 28 - the number of states with existing resolutions on the most common convention topic, a balanced budget amendment. Others point to lower total counts based on states that have passed near-identical resolutions.

Regardless, proponents of a convention believe they have momentum on their side more than any other time in American history.

"That second clause of Article V was specifically intended for a time like this, when the federal government gets out of control and when the Congress won't deliver to the people what they want," said Mark Meckler, a tea party leader who now heads Citizens for Self-Governance, which runs the Convention of States Project calling for an Article V convention. Legislation promoted by the group calls for a convention focused on the federal government's budget and power, and term limits for office holders. It has passed 12 states and one legislative chamber in another 10.

The Convention of States Project says 18 other states are considering the measure.

Meckler, like other backers of a convention, believes there's no reason why it can't be limited in scope. Others aren't so sure. Four states that previously had passed resolutions calling for a convention have rescinded them in recent years, often citing wariness over a "runaway" convention.

Karen Hoberty Flynn, president of Common Cause, has sounded alarms on a possible convention and portrays the coast-to-coast emergence of resolutions on the issue "a game of Whack-a-Mole."

"This is the most dangerous idea in American politics that most people know nothing about," she said.

Nancy MacLean, a Duke University historian and author of "Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right's Stealth Plan for America," views the prospect of an Article V convention with fear - the next chapter of decades of work on the far right transforming the federal judiciary and supporting cases that go on to make broad constitutional points, all while suppressing votes and gerrymandering districts.

"The ultimate project," MacLean said of conservatives, "is to transform our primary rules book, which is the Constitution."

It's not the first time a convention has been proposed.

In the 1890s, when the Senate refused to take up the issue of direct election of senators, states pursued a convention, falling just short. Eventually, the 17th Amendment passed in the usual way, fulfilling that aim. In the 1960s, states sought a convention over a Supreme Court decision dictating how legislative districts were apportioned.