The president of the League of Women Voters of Boone County-Columbia lectured on the history of voting in America on Thursday afternoon at William Woods University.

In conjunction with the LWV's 100th anniversary, chapter President Marilyn McLeod explored how American voting has changed since the late 18th century. The lecture was a part of the fourth diversity and inclusion symposium at WWU that took place Monday through Thursday.

"The funny thing is, in the constitution - which we revere - there is nothing literal that says every citizen has the right to vote," McLeod said.

McLeod outlined how during the early stages of American society, wealthy white men, who were property owners, were the only citizens allowed to vote. While voting rights began to expand in the 19th century, many new caveats were put into law to suppress votes from certain groups.

"In 1821, New York state revised its constitution and imposed on every man of color that they must have an estate that's valued at least $250," she said. "Of the 12,000 free African Americans living in New York City, only 68 of them could vote."

She painted a picture of the reality 19th century married women faced in which they were not allowed to keep their wages, domestic abuse was tolerated and it was difficult to get a divorce. She touched on some of the pushback of this reality and some of the early women-led movements to secure their ability to vote.

These events included the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, which was the first women's rights convention, and the 1874 Supreme Court case in which Virginia Minor unsuccessfully argued the 14th amendment gave women the right to vote. McLeod emphasized how many in power at the time felt women and other minorities did not have the "inherent ability to vote wisely or independently."

"Think about that," McLeod said. "Does that make you feel important? It basically dismisses everyone that isn't a white male and says that they're the only ones that can think."

McLeod noted once the 19th amendment was passed in 1919, securing women with the right to vote, Missouri ratified the amendment one month after it passed, something she considers "amazing." The constitutional amendment was fully ratified in 1920 after it passed in Tennessee by only one vote.

"Always remember that your vote matters," McLeod said.

The symposium's founder, Mary Mosely, shared a story of when she forgot to vote in a local election a few decades ago and a seat for city council had come down to a tie. She said the city had to pay to hold a run-off election, which she felt could have been completely avoided had she remembered to vote.

"The woman running for the seat was my son's social studies teacher, and he never lets me live it down to this day," she joked.

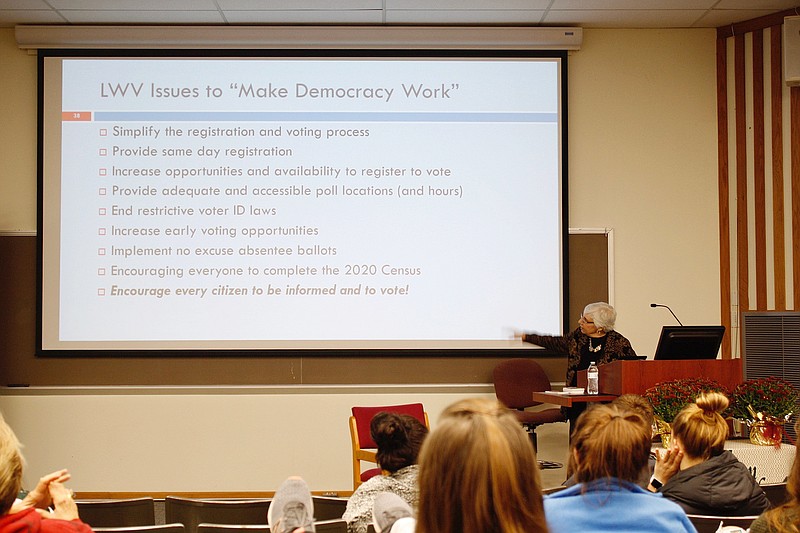

While voting liberties in America have vastly expanded in the 20th and 21st centuries, McLeod pointed out many contemporary practices she and the LWV view as "voter suppression." One in particular was the voter ID law passed in Missouri in 2016, which requires all registered voters to have a particular form of identification.

The Missouri Supreme Court earlier this month heard arguments challenging the constitutionality of part of the voter ID law. It has yet to issue its opinion.

"The League of Women Voters has argued against it and has actually filed several lawsuits against it because it's not a fair thing for all (Missourians)," McLeod said.

Some examples of the law being unfair, according to McLeod, include cases in which older voters let their driver's licenses expire once they stop driving. Without a valid driver's license, they would face extra hurdles to be eligible to vote.

She also pointed out how a woman could be ineligible to vote if she changes her name because of a marriage or divorce but does not update her proper identifications before an election.

"I tell a lot of young women today to just not change their names if they get married because it could potentially impact their ability to exercise their vote," McLeod said.