There’s little to no grass for livestock in southern Missouri.

Farmers are culling their herds to send to market while others have started feeding them hay, which usually doesn’t happen until the fall.

And wildfires are on the rise as more than 90 have been reported since June 1, consuming almost 500 acres of the state so far.

Nearly 75 percent of Missouri is in a drought, with 35 percent of the state experiencing severe to extreme drought.

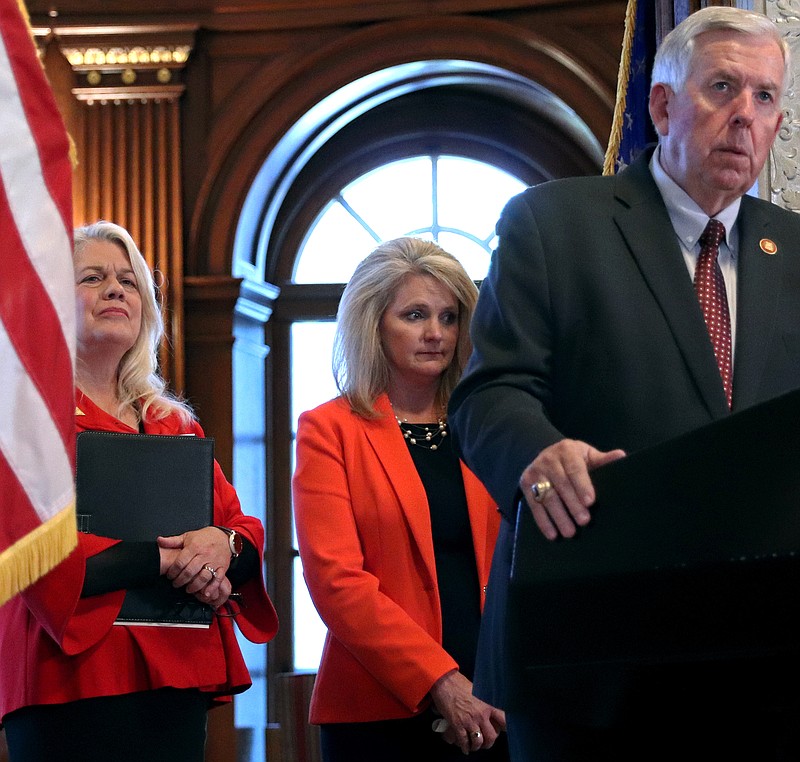

Drought conditions emerged in the southern part of the state and are beginning to impact parts of Central Missouri south of the Missouri River, Gov. Mike Parson announced with state agency officials Thursday.

“With temperatures near 100 degrees the rest of this week, it is not surprising that we’d be talking about drought conditions,” he said. “And, unfortunately, we don’t anticipate conditions improving soon.”

In response, Parson issued an executive order that: declares a drought alert for 53 of Missouri’s 114 counties, initiates a process for farmers to access water and hay from state parks and conservation sites, directs the Missouri Department of Natural Resources to form a Drought Assessment Committee, and directs all state agencies to review administrative rules and funding to assist communities.

The response is similar to how Missouri reacted to drought in 2018, which largely affected the northern half of the state.

“We’ve learned from past experience the more proactive we are, the better we can help our farmers and citizens lessen the impact of even the most severe droughts,” Parson said.

The Republican governor said his administration has reached out to the state’s federal delegation and national agencies for support. Parson said he’s confident federal assistance will come, but he doesn’t know what it will look like.

DNR Director Dru Buntin said he takes the job of administering Missouri’s drought response seriously. The agency is releasing daily updates with new drought maps and links to state and federal resources online at dnr.mo.gov/drought.

DNR is partnering with the Missouri Department of Conservation to open up more than 40 conservation areas and more than 20 state parks for livestock farmers. Available sites are identified in an interactive map on the DNR’s drought website.

Livestock producers who want to pump water from a conservation area need to contact the area manager to receive an expedited special-use permit. Farmers are required to bring their own water-hauling equipment.

Buntin said expansion into using other public water resources, such as community reservoirs, may come later.

“We hope it won’t be a prolonged drought, but we’ve got a great, dedicated team that will remain committed to serving citizens for as long as necessary,” Buntin said.

Water can be collected immediately, Buntin said, whereas the hay program isn’t quite ready.

The state is still considering how to roll out its plan for farmers to access state parks and conservation areas for hay, Buntin said, and could use a similar lottery-like system as 2018 if there’s widespread interest among farmers.

MDC Director Sara Parker Pauley said the state agency will work to quickly accommodate the needs of farmers.

“This is a severe situation for producers,” she said.

MDC is also responsible for wildfire suppression, Pauley said, and continues to work with more than 775 local fire departments to fight them.

Chris Chinn, director of the Missouri Department of Agriculture, said the drought may worsen conditions for farmers, who have been challenged with rising fuel and fertilizer prices and supply chain delays.

Valued at $93 billion, agriculture is the leading industry in Missouri with more than 95,000 farms planted in the state. Chinn said technological advancements like drought-resistant crops will help farmers survive extreme conditions, but concerns are still present.

Missouri has the third-most cow and calf operations in the United States and the drought’s effect on livestock will have “a huge impact on our markets,” Chinn said.

Corn crops in southeastern Missouri are withering before pollination, she explained, and large portions of Missouri’s cattle, cotton, rice and soybean industries are in drought areas.

“Of course this is very stressful on them, it’s stressful on their families, it’s stressful on that rural community,” Chinn said, adding drought effects will be felt throughout the agricultural community.

Parson said he’s committed to providing resources for what may be a months-long response to the drought. He said he doesn’t see the extreme weather as anything new, but something agricultural producers have and will continue to weather.

“We’re not going to be able to fix the problem,” he said. “We’re just going to be able to help with that.”