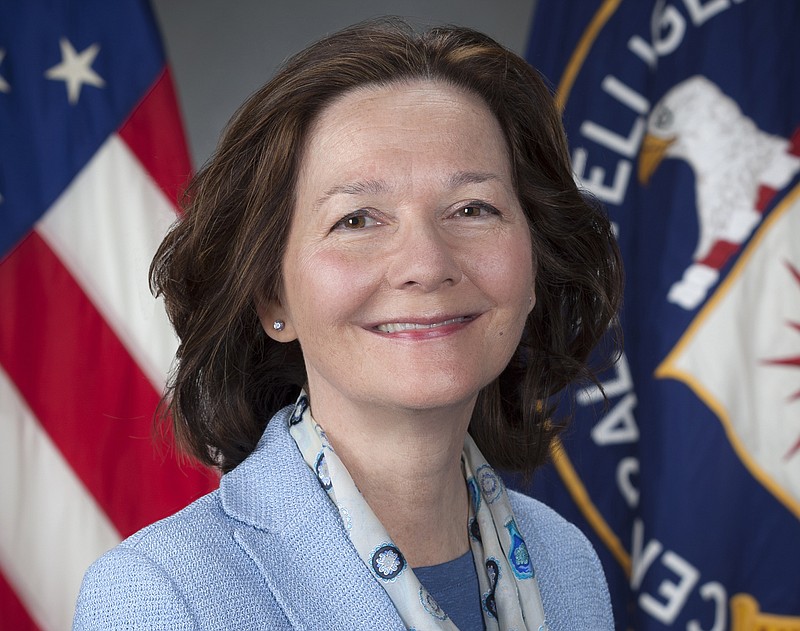

WASHINGTON (AP) - Gina Haspel's long spy career is so shrouded in mystery that senators want documents declassified so they can decide if her role at a CIA black site should prevent her from directing the agency.

It's a deep dive into Haspel's past that reflects key questions about her future: Would she support President Donald Trump if he tried to reinstate waterboarding and, in his words, "a lot worse"? Is Haspel the right person to lead the CIA at a time of escalating Russian aggression and ongoing extremist threats?

Haspel's upcoming confirmation hearing will be laser-focused on the time she spent supervising a secret prison in Thailand. The CIA won't say when in 2002 Haspel was there, but at various times that year interrogators at the site sought to make terror suspects talk by slamming them against walls, keeping them from sleeping, holding them in coffin-sized boxes and forcing water down their throats - a technique called waterboarding.

Haspel also is accused of drafting a memo calling for the destruction of 92 videotapes of interrogation sessions. Their destruction in 2005 prompted a lengthy Justice Department investigation that ended without charges.

"We should not be asked to confirm a nominee whose background cannot be publicly discussed and who cannot then be held accountable for her actions," said Sen. Martin Heinrich, who joined other Democrats on the Senate intelligence committee in asking the CIA to declassify more details about Haspel. "The American public deserves to know who its leaders are."

Court filings, declassified documents and books written by those involved in the CIA's now-defunct interrogation program suggest Haspel didn't arrive at the secret prison in Thailand until after one detainee, Abu Zubaydah, was waterboarded 83 times in August 2002. But they indicate she arrived before another detainee, Abd al Rahim al-Nashiri, was waterboarded at least three times in November 2002.

Details about the two detainees' treatment were disclosed in a 2014 Senate report. It said the prison was shut down in December 2002.

Even if Haspel was at the prison site for just a few months, Steven Watt, an American Civil Liberties Union attorney, said she was deeply involved in the interrogation program. For much of its existence, Haspel was deputy director of the CIA's counterterrorism center that ran the program using "enhanced interrogation techniques."

At least 119 men were detained and interrogated as part of the program, said Watt, who represented two detainees and the family of another in a 2015 lawsuit against a pair of CIA-hired psychologists.

It's unknown if Haspel ever was or currently is a gung-ho proponent of brutal methods, or if she was only implementing orders from CIA headquarters.