When Dr. Barbara Kerr was a University of Missouri student, she often found herself mixing with Westminster students. Once, they were in a pitch black cave.

"There are a lot of caves around here, right?" she asked her audience at her keynote Hancock Symposium address, "Bottled Lightning: The Psychology of Creative People."

Students interested in all kinds of subjects were quietly talking in the dark - and that left Kerr feeling a bit out of place.

"I was thinking, 'I want to be creative like these people,'" she said. "I was not an artist, but I discovered I had a creative gift working with creative people."

That's how she's spent her life: Studying the brains of creative people.

Kerr holds an endowed chair as distinguished professor of counseling psychology at the University of Kansas and is an American Psychological Association Fellow. Her M.A. from the Ohio State University and her Ph.D. from the University of Missouri are both in counseling psychology. She currently directs the Counseling Laboratory for the Exploration of Optimal States at the University of Kansas, a research through service program that identifies and guides creative adolescents.

Early on, she helped members of the Iowa Writer's Workshop.

"I worked with writers and they needed me," she said.

Kerr and her teams have spent years working with creative people. She's studied inventors and architects, children and holy people of Southwest native tribes.

"I recently went with a research team to Iceland," she said. "We went with one question. Why is Iceland so creative?"

One obstacle: Many Icelanders don't think they're exceptionally creative. But starting their kindergarten years off with innovative educations, performing school and community projects such as building playgrounds, they think that's normal.

"They complain all the time; they're never satisfied," Kerr said. "They're independent, and they think things can be better."

That's not how it works here in the United States, however. Less funding is put into creative subjects - arts and music and writing education - and Americans are lagging behind the rest of the world.

Kerr cited results after the No Child Left Behind Act was signed into law in 2001 with bipartisan support. The law "ensured" students in every classroom achieve important learning goals - but those goals were for everyone, trying to level the playing field.

"It was teaching to the lowest common denominator," Kerr said, adding it left little room for students with differences.

And creative people are different, she said. A student interested in video games may have little interest in math. A child interested in science may not care about athletics. Yet public schools expect every child to perform the same in every subject.

It's not working well, she added.

"Creative young people have experienced a decline in mental health in recent years," she said. "They truly are the canaries in the coal mine."

That's not always been the case.

"Creative people have always been very well adjusted until about 10 years ago when we noticed sudden changes," Kerr said. "We ignored our creative people for so long."

Kerr directs CLEOS at the University of Kansas, providing counseling and career development to creative adolescents and adults while studying their characteristics and needs.

"We want to guide creative people," she said.

She said she's come to some conclusions. One, there are many blocks in the paths of creative people. There's anxiety and depression, and isolation, too.

"Another block is stupid relationships," Kerr added.

Apparently, psychologists often disagree on the theory of what makes people tick, or stop ticking. But, Kerr said one thing most agree on is the definition of intelligence. It's pretty simple.

"Intelligence is the ability to catch on, make sense of things, and know what to do about it," Kerr said. "Intelligent people engage in divergent thinking - being able to generate ideas that are original and that work. They are open to experience: curious, independent, alive to their senses, and always noticing smells and tastes."

Creative people aren't good at everything, nor should they be.

"If they are passionate about something, they give 100 percent," Kerr said. "They're B students; not A students."

And there's one more criteria when thinking about a person's ability to be creative. She called it the "flow state." Others might call that zen.

"It's when you're at one with what you're doing," Kerr explained. "You lose track of time. It's like bliss. And you want to go back to it, time and time again."

Creative people have an intense focus and typically expertise in one domain, resulting in uneven achievement. Creative people often have high energy levels and might not take care of their health, eating and sleep habits as well as they should.

They probably need a partner that grounds them.

"As a creator, you don't need to have social skills. You just have to have partners who do," Kerr said, laughing. "It takes just one best friend, but find a group of people, and find your city. If you're a writer, you want to go to New York City where there are agents and publishers."

Kerr also talked about privilege and how that allows a person to give into their creativity.

"Privilege is part of the equation," she said. "Minorities are underrepresented. Gender matters."

Kerr added just 18 percent of inventors are women. And on a recent trip to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City with her children, she discovered only 8 percent of the paintings were by women.

Kerr has a bunch of books out people can read to learn more.

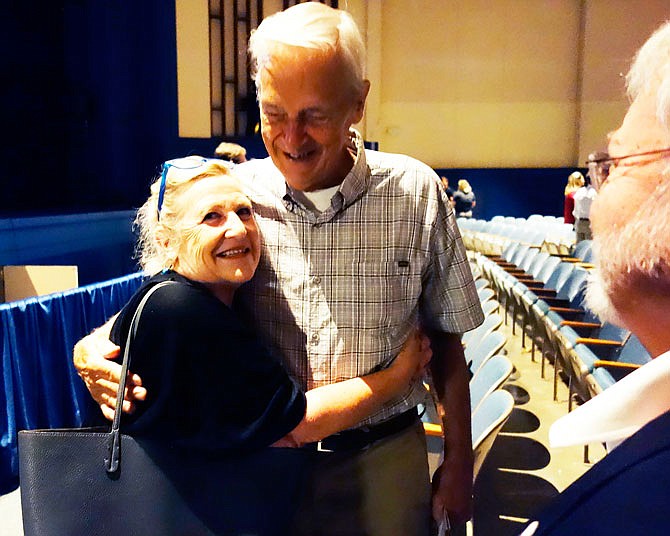

"I'm easy to find," she said after the lecture, laughing.

She ended her talk on a high note.

"My hope is for you to find creativity in yourself and find it in other people," Kerr said. "And become a society of innovators."