Haints aren't quite the same as ghosts, according to Matthew Dube, English professor at William Woods University.

Haints - which is essentially southern slang for a haunt or spirit - are a major plot point in "The Turner House," by Angela Flournoy.

"I grew up in Massachusets, so I'm pretty New England," Dube said. "If you'd asked me what a haint is, I wouldn't have known the word. But my wife, who's from north Georgia, definitely would."

William Woods University hosted the first lecture of One Read Tuesday, led by Dube. Throughout this month, the Callaway County Public Library coordinates events related to the One Read book. It's like a community-wide book club. This year, the chosen book was "The Turner House."

The book's central character, a black man nicknamed Cha-Cha, spends the book trying to understand the haint that first appeared to him when he was 14 is back to haunt him at 63. He does so through therapy and by researching his own heritage. As it turns out, there's a rich tradition of African-American folklore around haints.

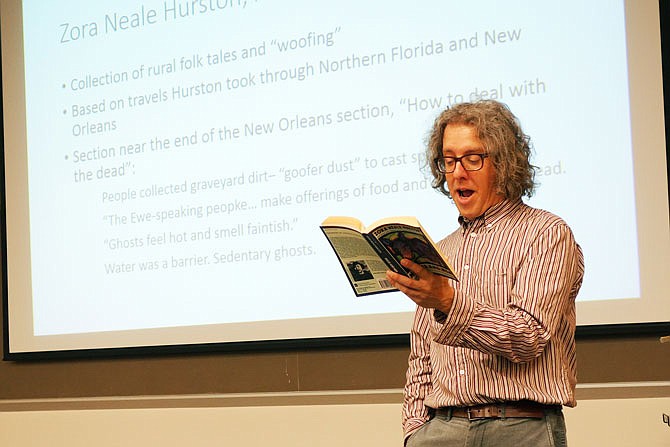

Dube discussed some of that tradition in his lecture.

"I discovered there's a shade of house paint called 'Haint Blue,'" Dube said. "It's like a legit Sherman-Williams paint color."

Through out the south, and particularly in the Carolinas, many porch ceilings are painted a light blue. It's a long-standing tradition, Dube said, and the reason may be an old belief that haints couldn't cross water - water is blue, so blue paint might trick them to keep away.

Dube talked about several folklorists who collected tales from the south. Many of these stories dated to the Civil War and many involve haints.

He mentioned Zora Neale Hurston, Frank C. Brown and Richard M. Dorson. Dorson published a collection of these tales called "American Negro Folktales" in 1956. He learned many of the stories from a man called J.D. Suggs.

"Suggs is this interesting character," Dube said.

An African-American born in 1897 in Mississippi, he had a fantastic memory for stories. During the course of eight visits, Suggs passed on 175 tales to Dorson.

"Suggs proved the best storyteller I ever met," Dorson wrote.

Hurston's collected stories also mentioned haints. Some were benevolent, others needed to be warded away.

In "The Turner House," the haint first appears to Cha-Cha after he moved into his new room. Many hauntings seem to be tied to specific places, Dube said. Others are tied to people, as Cha-Cha's seems to be once it reappears in adulthood.

"I think there's a powerful emotional need," Dube said. "People who are visited by ghosts often have unfinished business."

Dube ultimately raised a question: Are the haints of southern and African-American folklore different than other ghosts? Many haint stories are tied to the Civil War, a time when many black Americans were enslaved and sometimes forcibly separated from family members, he said.

"Perhaps you need different things when you think about loved ones you're torn away from," he said.